Behaviour Settings to Capture Normativity in the Wild

Author: Giulia Di Rienzo (UA)

The following REPAIRS toolbox is available under the CC-BY licence (Creative- Commons: https://creativecommons.org/). This implies that others are free to share and adapt our works under the condition that appropriate credit to the original contribution (provide the name of the REPAIRS consortium and the name the authors of the toolbox when available, and a link to the original material) is given and indicate if changes were made to the original work.

A Primer and Toolbox for Observation

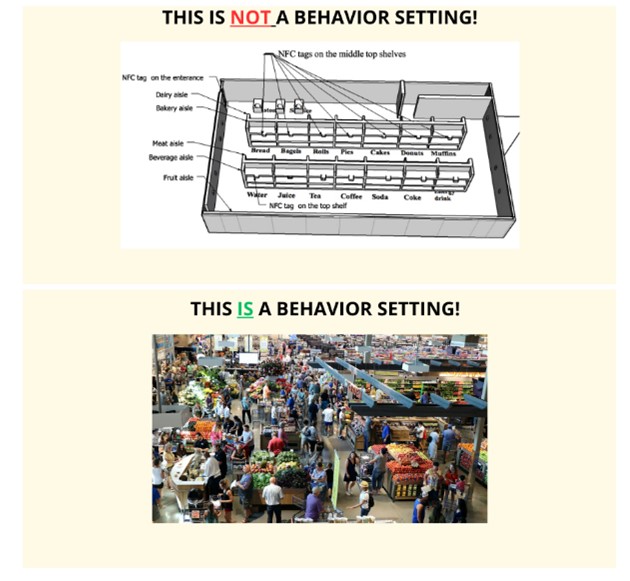

- What are behaviour settings?

Originally developed by Roger Barker and colleagues (1969), behavior settings are powerful tools for analyzing how environments shape human activity. They are not just physical spaces or mental categories, but emergent structures where actions, objects, and spatial arrangements interlock to form predictable patterns of behavior. These settings are extra-individual, shaped by collective practices and material features, and help explain why people behave in context-specific ways, supermarket, classroom, waiting-room. Each behavior setting consists of:

- A standing pattern of behavior

- A milieu (a specific time-place-object configuration)

When these elements interlock, they form a synomorph, or what we call a “place for action”, the interface where behavior and environment meet.

2. Behavior Setting as a Methodology

Beyond their conceptual value, behavior settings offer a practical methodology for studying how environments shape behavior (Lucas, 2024). Barker’s work laid out systematic methods for identifying, describing, and measuring these settings, later refined by Schoggen (1989). Behavior settings are treated as empirical units, defined by:

- Structural properties (e.g., layout, boundaries, components)

- Dynamic properties (e.g., patterns of activity, interdependence)

Box 1. The Structural Side of Behavior Settings

To identify potential behavior settings:

1. Observe physical structures, walls, doors, partitions, as the “exoskeletons” of behavior settings

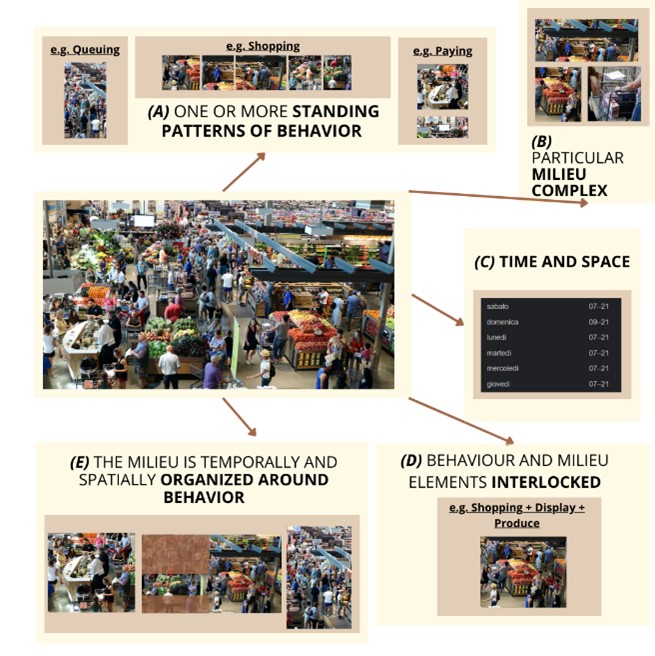

2. Apply the structural test to determine if a space qualifies as a place for action (synomorph). It must (see Figure below for visual representation):

a. Contain one or more standing patterns of behavior

b. Be tied to a specific milieu (time-place-object)

c. Be anchored in a sepcfici time and place

d. Show structural complementarity

e. Be physically and temporally enclosed by the environment

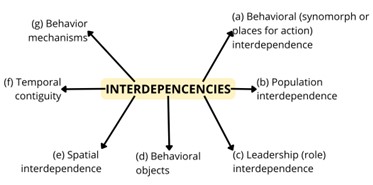

Box 2. The Dynamical Side of Behavior Settings

The K-21 test helps determine whether two places for action are independent settings or interdependent parts of a larger one. It evaluates seven dimensions of interdependence:

- Behavioral Interdependence – Do actions or their effects (e.g., sound, smell) cross between settings?

- Population Interdependence – Do the same people use both settings?

- Spatial Interdependence – Do the physical spaces overlap?

- Temporal Contiguity – Do the settings occur close together in time?

- Object Interdependence – Are objects shared or functionally similar?

- Similarity of Behavioral Patterns – Are the same types of actions dominant in both?

- Results – A total score < 21 suggests one integrated setting; ≥ 21 suggests distinct settings.

3. Beware of the Pre-Formationist Ghost

Behavior settings are normatively specific; they guide how we act based on their structure. But this normativity is not fixed or programmed. While early theories saw settings as implementing a “program” of eco-behavioral events (Barker, 1968), this view has been critiqued for ignoring how settings evolve over time.

Recent research reframes behavior settings as emergent and performative, shaped by the ongoing coordination of people, objects, and temporal rhythms. Tools like the K-21 test help identify structure, but we must avoid treating settings as static. Instead, normativity is performed and sustained through repeated, situated activity.

3.1. A different take on the structural and dynamical test

A key lesson from observing behavior settings within REPAIRS is that their normative specificity emerges through the temporal coordination of distinct synomorphs (Di Rienzo et al, 2024). These places for action are not isolated; they interlock to sustain the setting over time.

Example: The Grocery Store

The activity of “doing the shopping” unfolds across a longer timescale than individual actions. Yet, selecting produce, comparing prices, and checking out are functionally distinct and normatively specific. Each synomorph (e.g., produce section, checkout) invites particular behaviors, and together they coordinate to sustain the larger setting. Thus, the grocery store is not just a container for behavior; it is a temporally extended, collectively organized process. Its normativity is performed, not pre-programmed.

4. Conclusion

Treating behavior settings as static structures risks obscuring what they reveal best: how people, things, and practices stick together and mutually reinforce over time. A forward-looking, process-based approach allows us to observe how emergent forms are made to last, how normativity is not just followed, but actively maintained through everyday coordination.

References

- Barker, R. G. (1968). Ecological Psychology: Concepts and Methods for Studying the Environment of Human Behavior. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Lucas M. (2024). A practitioner’s field guide to the behaviour settings method. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 379(1910), 20230285. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2023.0285

- Schoggen P. 1989 Behavior settings: a revision and extension of Roger G. Barker’s ecological psychology. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. (doi:10.1515/9781503623149)

- Di Rienzo, G., Myin, E., & van Dijk, L. (2024). Navigating the normativity of behaviour settings: an observational case study. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 379(1910), 20230295. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2023.0295